The Influence of Mainard the Fleming on the Character of St Andrews

One of the goals of this blog series is to identify and discuss people of Flemish origin who have had a noteworthy impact on Scotland. In this blog article, Robin Evetts, our first guest blogger, examines the influence of Mainard the Fleming on the character of St Andrews. Robin wrote a PhD thesis on the 19th century development of St Andrews in the 1980s, and was formerly a Senior Inspector of Historic Buildings with Historic Scotland. He maintains his interest in the history and protection of St Andrews, and is a Trustee of a number of local and national historic building related organisations.

————————————-

The historic built character of St Andrews as generally perceived consists of ecclesiastical ruins, churches, university buildings of various types, and houses and other buildings of differing sizes, styles and dates, all contained within and governed by a distinctive wedge shaped town plan. But such a town plan did not always exist. The Culdee settlement to which Mainard the Fleming came in the 12th century had been in existence since at least the 8th century, and research by Professor Leslie Alcock and his wife Elizabeth in the 1990s underlines, if not confirms the already established interpretation that this monastic and adjoining lay settlement was on a north south axis approximately comparable with North and South Castle Street, possibly focussing on a kind of royal residence on the site of the castle.[[1]] The settlement appears to have been divided into several sections: a vill (or township) near the castle and a clachan (market settlement) to the east of North Castle Street and the north of North Street, perhaps with a market place; an area due south to the east of South Castle Street for scolocs, or scholars associated with the monastic foundation, later to incorporate the site of the Archdeacon’s Manse (now known as Dean’s Court, opposite the Cathedral); further south again, south of the east end of South Street, an area associated with the St Leonard’s pilgrim hospice, later to be St Leonard’s College (from the late 19th century, St Leonard’s School); and to the east, on the site of the Cathedral and Priory an area referred to as associated with the ‘economy’ of the monastic community.[[2]] The north south alignment of this early settlement, known as Kinrimund, or Kilrymund is often overlooked in historic descriptions of the town, but the tower of the reliquary church of St Regulus, erected in c.1080 remains as its greatest and most remarkable architectural manifestation, and one of the focal points of the existing town plan.

The origin of the development of the Culdee/Kinrimund settlement on its more familiar east west axis dates to 1124-44 during the reign David I (son of Malcolm III Canmore and Queen, later Saint, Margaret). Bishop Robert (episcopate 1124-59) was appointed by the king from the Augustinian house at Scone to reorganise the existing monastic community on Augustinian lines, and to establish a burgh of St Andrews. Mainard, who had been the king’s burgess at Berwick and is credited with having laid out its plan, was appointed as provost, and granted three ‘tofts’ of land to the east end of what is now South Street (probably the sites currently occupied by South Court, Great Eastern, and the corner block with Abbey Street).[[3]] This seems to have established the now familiar pattern of burgage plot development, normally about ten paces wide, but in the case of these three plots significantly more. So began the development of South and North Street westwards, both probably following existing tracks but providing appropriately wide and impressive processional routes to the new Cathedral planned by Robert and begun by his successor Arnold in 1160.[[4]] From this time, the name St Andrews came to be used for both monastic and lay settlements.

Until the 15th century, only the ecclesiastical buildings were constructed of stone, although the Archdeacon’s Manse seems to have been an exception where a ground floor vault which may be of the 12th century survives.[[5]] Excavations at 24 South Street in 1970 and at 67-69 South Street (St John’s House) in 1972 showed that domestic buildings were originally of timber, and wattle and daub, with thatched roofs.[[6]] Nicholas Brooks, who excavated St John’s, concluded that it was entirely rebuilt in stone in the mid 15th century, and that business or trade was conducted on the ground floor with living accommodation above.[[7]] Evidence of this kind of development is apparent elsewhere, such as 52 South Street where there is a vaulted ground floor chamber with original chamfered doorpiece set-back the depth of a room (the original foreland) from the current building line. A similar set-back vaulted chamber was uncovered at 47 South Street during the 2000s, and there are other examples in South Street and at 71 and 75 North Street, all of which would appear to date from the 15th century, with later upper floors and additions, and subsequent alterations.

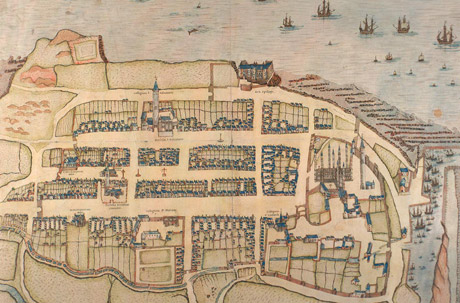

Market Street and the linking cross streets and wynds emerged as the burgh developed westwards, and by the 16th century, when depicted in the panoramic view by John Geddy,[[8]] St Andrews had reached the peak of its mediaeval cultural development, and was ‘one of the great historic cities of Europe’.[[9]] The view shows the town with a remarkable concentration of ecclesiastical and educational buildings, dominated in the east by the Cathedral, St Rule’s Church, the Priory and Archbishop’s Palace, and associated buildings; in South Street the Church of the Holy Trinity, the religious house of the Blackfriars and the colleges of St Leonard and St Mary; in North Street the college of St Salvator; and in Market Street the Greyfriars’ monastery. Civic life and the authority to trade is reflected in the tollbooth, market cross and tron in the centre of Market Street and the fish cross in North Street, and the dwellings and trading places of the populace shown in houses facing onto the principal and secondary thoroughfares, and in adjoining closes and wynds, laid out in distinctive burgage plots or rigs, as initiated by Mainard in the 12th century. All this is encompassed within perimeter walls, boundaries and ports, which if not defensive are at least protective, and close to the harbour, vital for communication and trade.

One of the remarkable features of St Andrews is that the plan with which Mainard is so closely associated, and its subsequent extension has survived virtually intact. Moreover, many of the most significant historic buildings, or substantial parts of them, remain. Mainard’s great contribution therefore, in association with Bishop Robert, was to initiate a formula or template whereby the subsequent development of ecclesiastical, university, civic, domestic, trade and service buildings could be appropriately and handsomely accommodated, as if to a master plan, while retaining the dominance of the Cathedral and its precinct. This east-west, wedge shaped plan has become one of the town’s defining historic characteristics.

The article above is based upon part of an informal talk given at the Strathmartine Institute in St. Andrews during April 2013. The article also draws on a talk by Dr John Frew for the St Andrews Preservation Trust in 2010. The text owes much to articles by various authors as cited below, but particularly to those by Dr Ronald G Cant, founder of the Strathmartine Institute. The reader is encouraged to consult these articles for a much more detailed discussion on aspects of the pre-Reformation development of St Andrews.

Robin D A Evetts

October 2013

20th century plan of St Andrews (http://www.greyfriars-garden.co.uk/images/Location.gif)

16th century panoramic, or ‘birds eye’ view of St Andrews (http://digital.nls.uk/golf-in-scotland/elite/geddy-st-andrews.html)

References

[1] Ronald G Cant, ‘Burgh Planning and early Domestic Architecture: the Example of St Andrews (c.1130-1730)’, in Deborah Mays, ed, The Architecture of Scottish Cities (1997), p.1. See also Cant’s articles in St Andrews Preservation Trust, Three Decades of Historical Notes (1991)

[2] Ibid, note 3.

[3] Ibid, p.1; Ronald G Cant, ‘South Court, St Andrews and its Renovation’ (1973), in Three Decades of Historical Notes, op.cit. p.67; Sir Archibald C Lawrie, Early Scottish Charters (1905), CLXII p.124, CLXIX pp.132-33 and pp.394-95

[4] The Scores, to the north was not developed in its present form until the 19th century. The 16th century panoramic view shows it as a route to the Castle, outwith the perimeter of the burgh.

[5] Cant, ‘Burgh Planning…’ op.cit.p.4.

[6] Anne Turner Simpson and Sylvia Stevenson, Historic St Andrews, Scottish Burgh Survey (1981).

[7] Nicholas P Brooks, ‘St John’s House: Its History and Archaeology’ (1976), in Three Decades of Historical Notes, op.cit. p.91

[8] Robert N Smart, ‘The Sixteenth Century Bird’s Eye View Plan of St Andrews’ (1974), in Three Decades of Historical Notes, op.cit. p81. Smart dates the plan to the early 1580s.

[9] Ronald G Cant, St Andrews, The Guide and Handbook of the St Andrews Preservation Trust (1982), p5.