The Fleming Family Charter Collection and the Dark Side of Fifteenth-Century Family Life

The collection of charters gifted by Eric Robertson to the University of Toronto’s Thomas Fisher Rare Books Library was the subject of a blog posting by Anne Dondertman and Alex Fleming on 13th March 2015. These charters make available additional material concerning the Fleming family between the fourteenth and sixteenth centuries. In this posting Professor Michael Brown examines one of these charters and reveals what might be construed as the dark side of the Flemings’ fifteenth-century family life.

Background

Digital images of an initial two of these documents have been made available to the University of St Andrews Institute of Scottish Historical Research and give a taste of the wider collection that comprises sixty charters. The earlier of these two (which is reproduced in the 13th March post) is a charter granted by Malcolm Fleming lord of Biggar to his younger son, Patrick, in 1395. The document transfers legal possession of Malcolm’s lands of Glenrusto and Over Menyean in the valley of the Tweed to Patrick.

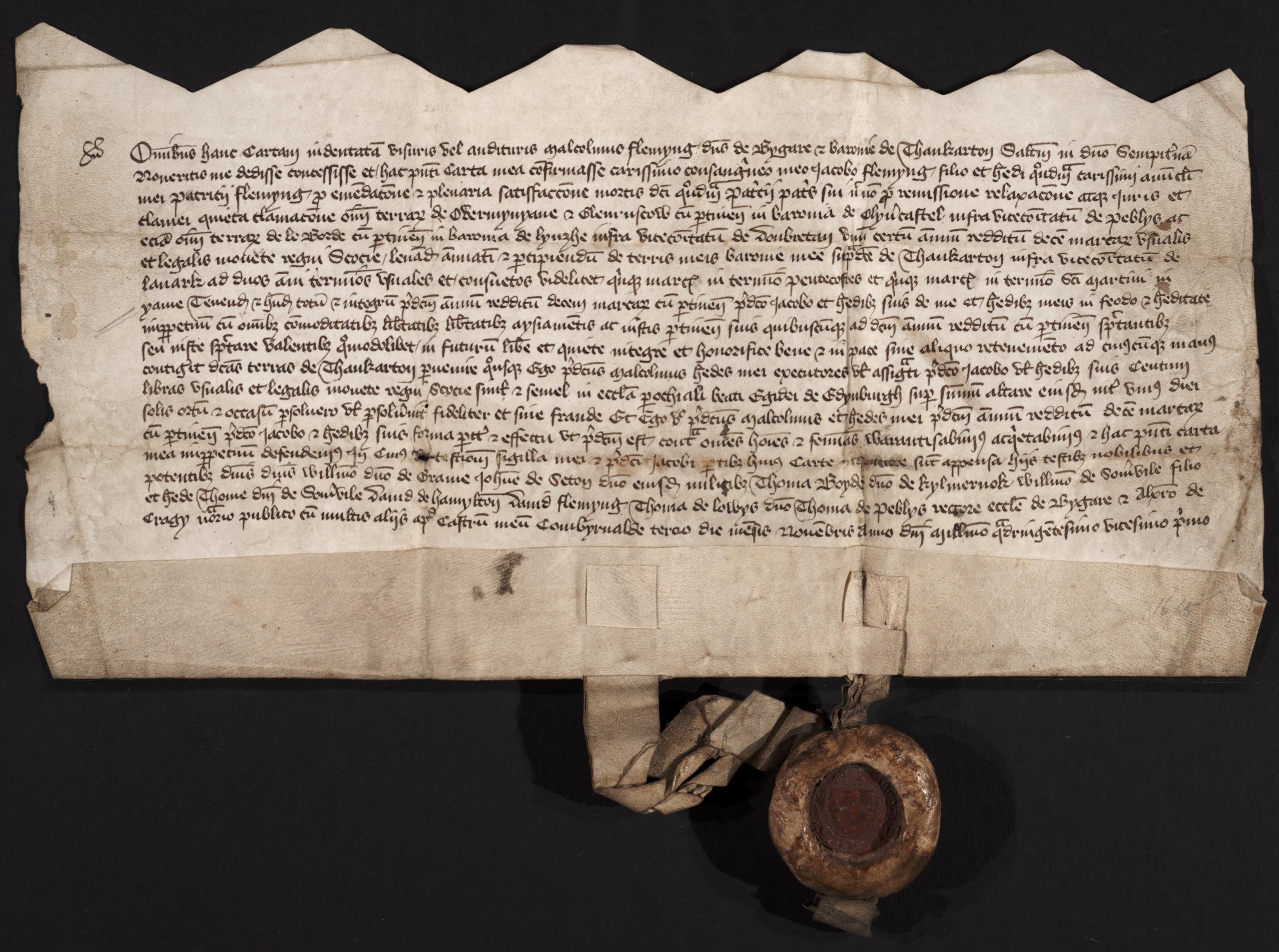

The second document (shown above), which is dated 3rd November 1421 and issued from Cumbernauld Castle, is effectively a sequel to this. It too is a charter but, as the serrated top edge of the document shows, was produced as one part of an indenture or agreement. Two versions of the document would be written. One would be kept by each party. The indented edge would prevent one side forging a new version. Common in contracts or personal agreements where squabbles over terms might be expected, it is unusual to find this feature being used in charters that transferred or confirmed legal rights in the most formal terms. The content of the document doesn’t, on the face of it, seem particularly controversial. It is from Malcolm, grandson of the Malcolm who was a party to the 1395 charter (noted above), to James, his cousin and the son of Patrick, the recipient of the lands in this earlier grant. Like the 1395 charter, it involves a transfer of land within the Fleming family and some of the property mentioned is the same. The charter is written in a fine, clear hand and begins

Malcolm Fleming lord of Biggar and of the barony of Thankerton to all those who see or hear this indented charter greetings in the name of the eternal Lord. Know that I give, grant and in this my present charter confirm to my dearest cousin James Fleming the son and heir of my late dearest uncle Patrick Fleming, for the resignation, release and quit claiming of right and claim to all the lands of Overmynyane (Menzian) and Glenruscow (Glenrusco) with its pertinences in the barony of Oliver Castle in the sheriffdom of Peebles and all the lands of le Bord (Board) with pertinences in the barony of Lenzie in the sheriffdom of Dumbarton, a certain annual rent of ten merks of the usual and legal money of the kingdom of Scotland to be raised annually from the lands of my barony of Thankarton (Thankerton)…

Documents like these – formal records of transactions involving land and annuities – represent the vast bulk of the evidence for medieval Scotland outside the records of royal government. At first glance, they seem pretty dry stuff. However, within them lies our best chance of glimpsing issues involving the land, family fortunes, personal relationships and local life in the medieval kingdom. The legal phrases of the charter of 1421 between Malcolm Fleming lord of Biggar and his cousin, James, are deceptively bland. Beneath them lies a story of family conflict and even violent kinslaying that can be teased out and which fuller examination of the Fleming charters may illuminate further.

The Fleming Family in its Charters

The charters in the Robertson Collection should contribute to our understanding of the Fleming family in the early fifteenth century. They can be added to the collection held in the National Library of Scotland that derived from the papers of the Flemings of Biggar, from 1451 Lords Fleming and, after 1606, Earls of Wigtown.[1] An inventory made of the family records in 1681, and calendared by the Scottish Records Society in 1910, shows the Flemings of Biggar to be a significant and well-connected baronial family in the period. Their estates were concentrated in south central Scotland, in particular the baronies of Cumbernauld, Kirkintilloch, Lenzie and, a little further south, Biggar.[2] To think of a lord like Malcolm Fleming is to think, in today’s terms, of the head of a landed corporation. He and his family derived their status and wealth from property and as custodian of these estates Malcolm had a responsibility to preserve, enlarge and pass on both land and rank to his heirs. The wider Fleming family was an element in these structures, but junior branches were not necessarily a straightforward source of friendship and support. As the charter from 1395 showed, the elder Malcolm felt an obligation to provide for his younger son from his property. However, a quarter-century and two generations later such paternal generosity was not regarded in such positive terms. Instead, the document of 1421 was one of the outcomes of internal family conflicts that went directly back to the gift of the elder Malcolm to his younger son. Knowledge of these events can be obtained by placing the indented charter alongside the material held in the National Library of Scotland. The inventory provides clues as to what actually took place, but a fuller picture of the situation must await the availability of the remaining documents in the Fleming collection.

Cumbernauld Castle, November 1421

The published inventory shows that the charter from the Robertson Collection was not the only document produced at a meeting within Cumbernauld Castle on 3rd November 1421.[3] There were several other documents issued with the same date and place which dealt with the relationship between Malcolm lord of Biggar and Cumbernauld and his cousin James Fleming. These documents were produced at what must have been a significant gathering. The witness list on the charter itself attests to the presence of powerful barons like William lord of Graham, John lord of Seton and Thomas Boyd lord of Kilmarnock. At the same time as receiving this grant, James Fleming made a separate formal resignation of the lands referred to in the charter to his cousin. This included a penalty clause: should James, at a later date, quarrel with Malcolm over the latter’s rights to these lands, James was bound to surrender another estate, Monicabo in Aberdeenshire.[4] This clause is a strong pointer to the fact that what was going on in November 1421 was no simple property deal but involved a degree of coercion of the lesser man, James Fleming, by his more powerful cousin.[5]

Direct evidence of the extent of this coercion is provided by a final document. This is a copy of what is described in the inventory as a ‘writ’, a suitably vague term. In this, James Fleming clears Malcolm Fleming of Biggar and his accomplices of any part in the death of his father, Patrick Fleming, and agrees to end any hostility towards Malcolm.[6] This document would obviously repay further examination but even this record makes clear that the land transactions were associated with the killing of their previous holder. It is surely not a huge stretch to suggest that Patrick Fleming had been killed in a dispute over his estates and that, after his death, his son was being forced to surrender the lands in question to a man implicated in the killing. James’s concession may reflect his powerlessness. Malcolm was the head of his family. Moreover the lord of Biggar was the brother-in-law of the governor of Scotland, Duke Murdoch of Albany.[7] Amongst those present, Seton, Boyd and Graham were councillors of the governor, and Seton was Malcolm’s first cousin. In such intimidating company, James had little choice but to submit and to give guarantees about his own future behaviour. We might imagine the charters and other documents being issued within Cumbernauld castle, not in at atmosphere of legal business, but against a background of suppressed animosity and latent threat.

Ties of family could cut in a number of different ways in late medieval Scotland. This case shows not the benign patronage of the head of a kindred to his lesser cousins, but the lengths to which landowners would go to consolidate their property. This brief and preliminary study is meant to show that legal documents can be a window into the values and events of a lost world, as writers of quasi-historical epics like John Barbour. There is undoubtedly more to this story to be revealed and the analysis of the other documents in the Robertson Collection will be a vital part of this. It can appear that historical research depends on single, great discoveries. The body in the car park idea of research – specifically the recent discovery of the remains of the English king, Richard III, in Leicester – is perhaps an example of this. However, it is more normal to add smaller items to the existing body of evidence, like new pieces to an endless and endlessly complex jigsaw puzzle. The Robertson Collection is a new box of pieces for historians of late medieval Scotland to rummage through.

Professor Michael Brown

May 2015

Michael Brown is professor of Medieval Scottish History at the University of St Andrews. His books include James I (Edinburgh, 1994), The Black Douglases (East Linton, 1998), The Wars of Scotland, 1214-1371 (Edinburgh, 2004) and Disunited Kingdoms: Peoples and Politics in the British Isles, 1280-1460 (Harlow, 2013).

References

[1] This title was created for Malcolm Fleming of Fulwood in 1341 but was lost to his family in 1372. A second creation was made in 1606 to John sixth Lord Fleming. Though the relationship between the printed inventory and the collection in the National Library of Scotland is not straightforward, initial research suggests that all the calendared discussed here are held in the library.

[2] Charter Chest of the Earldom of Wigtown, 1214-1681 and the Charter Chest of the Earldom of Dundonald, 1219-1672 (Scottish Record Society, 1910).

[3] In the Wigtown charter chest there is an indented charter with the same terms as the document in the Robertson Collection. Examination of this may confirm the possibility that it is the other part of the indenture (Wigtown Charter Chest, no. 249).

[4] Wigtown Charter Chest, no. 248.

[5] This might also be implied by the apparently unequal terms of the exchange of several properties for an annual payment of only ten merks.

[6] Wigtown Charter Chest, no. 406.

[7] Registrum Magni Sigilii Regum Scotorum, edd. J.M. Thomson and others, 11 volumes (Edinburgh, 1882-1914), i, appendix 1, no. 159; Wigtown Charter Chest, no. 247.

Background Reading

A. Grant, Independence and Nationhood (Edinburgh, 1984)

S. Boardman, The Early Stewart Kings: Robert II and Robert III (East Linton, 1996)

M. Brown, James I (Edinburgh, 1994)

"... more to this story to be revealed ..." well, in today's terms, there would necessarily be police and court records to reflect the underlying feud. However, these barons being themselves often law enforcement and the judicial branch of government as well, maybe there are no such separate and "objective" records? Otherwise there should have been indictments or inquests or any other form of official documentation of the alleged "kinslaying" etc.