Berwick-upon-Tweed and the Torching of the Red Hall

In this first posting devoted to examining the Flemish influence in different parts of Scotland, Jim Herbert looks at Berwick-upon-Tweed and in particular the torching of the Red Hall that has been the subject of varying accounts in books on Scottish history. While Berwick is no longer a part of Scotland, its geographic location on the border of Scotland and England resulted in it changing hands over time. The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of the University of St Andrews Institute of Scottish Historical Research.

Berwick’s story possibly begins in the 9th century. The name comes from the Viking “Berevic” meaning “barley farm”. Berwick is mentioned as early as 833 when a Danish king, Oseth, attacked Bernicia.[[1]] There are other mentions of Berwick in the 870s,[[2]] then part of the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Northumbria. A Saxon village called Bondington existed north of the area Berwick then occupied by the river Tweed. What the relationship between the two was is unknown. One theory is that “Berwick” was a fishing area used by the people of Bondington that then grew in importance while Bondington’s fortunes declined. The earliest contemporary and reliable mention of Berwick can be found in a charter created by King Edgar of Scotland in 1095[[3]] in which the town is granted to Bishop William of Durham.

In 1113, with the backing of Henry I of England, David (later David I of Scotland) became Prince of Cumbria, an area encompassing the Borders and Lothian. Within his new power base, David founded the Border abbeys of Dryburgh, Selkirk, Kelso, Melrose and Jedburgh. David made Berwick a Royal Burgh by 1119 and this indicates that the town must then have been one of great importance.

The Tweed valley provided excellent pasture for sheep farming that led to the development of the wool trade with Flanders. One of the earliest mentions of the Flemings dates from 1248 when Alexander II instructed Robert Bernham, then Mayor of Berwick, not to stop foreign merchants coming to Coldingham Priory (near Berwick) to buy wool and other goods.[[4]]

Another piece of evidence regarding Flemish settlement about this time is the village of Flemington,[[5]] situated a little to the east of Ayton. Not much is known about it. Now it is merely a farmstead but there is evidence of a tower house, and in 1583 it is recorded that certain houses in the “toun” of Flemington were burnt,[[6]] suggesting a settlement of some sort existed earlier.

Berwick was at the height of its prosperity in the late 13th century, during the reign of Alexander III. His death in 1284, the eventual crowning of John Balliol in 1292, and Balliol’s subsequent downfall led to Edward I’s invasion of Scotland which began at Berwick on 30th March 1296. Possibly the best-known story involving the Flemish merchants resident in the town at the time – that of their Red Hall – stems from this very bloody episode of Berwick’s history.

Yet much of the accepted story probably owes as much to the imagination as history. The Red Hall is first mentioned in “modern” histories of Berwick in Dr John Fuller’s History of Berwick (1799). All that is said is that the land of the Red Hall was given to the Flemish merchants in exchange for their pledge to defend the town against the English, and that when Edward I attacked the town thirty of them held the Red Hall for a day before it was burnt to the ground, killing them all.

The young John Mackay Wilson, who wrote a romanticized account in the early 1830s, would certainly have read this history. He wrote:

“This state of prosperity it owed almost solely to Alexander III, who did more for Berwick than any sovereign that has since claimed its allegiance. He brought over a colony of wealthy Flemings, for whom he erected an immense building, called the Red Hall (situated where the Woolmarket now stands), and which at once served as dwelling-houses, factories, and a fortress. The terms upon which he granted a charter to this company of merchants, were, that they should defend, even unto death, their Red Hall against every attack of an enemy, and of the English in particular.”[[7]]

This, in turn, was likely to have provided material for John Rennison’s Border Magazine (vol. 1) (1833)[[8]] and Frederick Sheldon’s History of Berwick-upon-Tweed (1849). Sheldon’s “sketches” of Berwick’s history are written in an equally romantic style, even embellishing Wilson’s version of events!

One of these is the notion that it was named after the reddish local sandstone – that is not impossible. However, another description with a theory about the colour is:

“Probably the greatest of the “halls” in Berwick was the Red Hall of the Flemings. Certainly it is the most frequently mentioned and was a factory with its own palisading and trench. It would have had two or three inner courts smeared with red paint as was the custom of the Low Countries.”[[9]]

The original accounts however bear out Fuller’s version of events.

“And soon, the trumpets sounding, they [the English] crossed as nothing an embankment which the Scots had made with boards, and attacked the enemy, slaughtering them from here to the sea. The Scots were astonished by their onset, and there was not one of them who raised a sword or threw a spear, but they stood dumbfounded like men beside themselves. But thirty Flemings, who had received the Red Hall on condition that they should defend it against the English King at all times, defended the house manfully until evening, but at length it was set on fire, and they were burnt with it…”[[10]]

and:

“But Flemish merchants who had a very strong house in that town, in the manner of a tower, threw bolts and spears at the English, and by chance struck Richard de Cornubia, the Earl of Cornwall’s brother, with a dart; and since it was not easy to get at them, fire was brought, and they were destroyed by the flames.”[[11]]

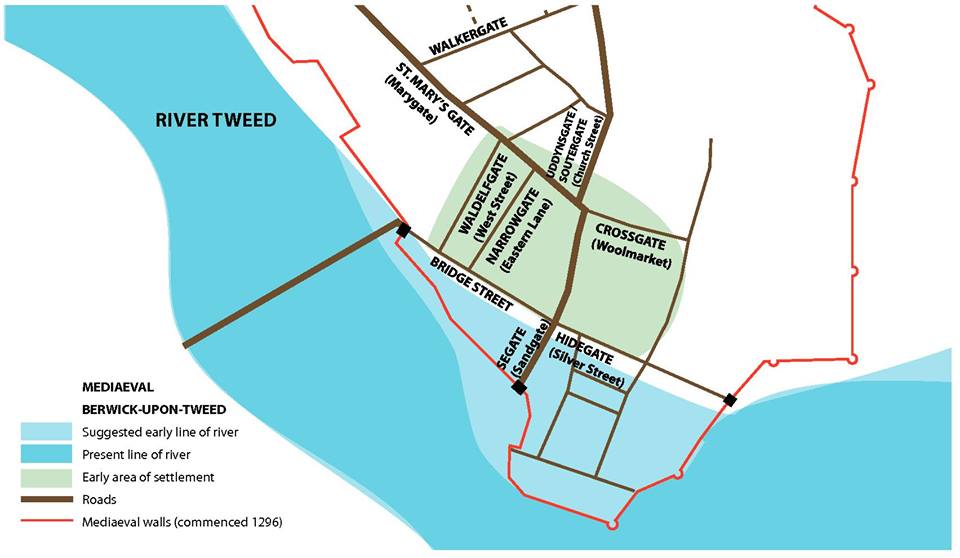

There is no evidence for the Red Hall being located in Woolmarket as suggested by Wilson, presumably because of the association with wool (the medieval name for this Woolmarket was Crossgate).[[12]] It is far more likely, however, to have been located in the area now occupied by Bridge Street. It is theorized that long before the medieval walls were built, the River Tweed flowed along what is now Bridge Street and that over time land was reclaimed allowing warehouses to be built serving the port. The Flemings were not, incidentally, the only overseas traders in the town. The White Hall belonging to merchants from Cologne was located in Segate, the medieval equivalent of today’s Sandgate that leads through the walls at the quayside.

Assuming that it is a reference to a replacement building in the same location, a clue comes from about 1314 when we are told that the wall needs to be repaired between John de Weston’s house and the Red Hall and from the Red Hall to the Segate. The Red Hall (Rodehawell) is also mentioned in a document of works as late as 1445 but whether by then there was still any Flemish involvement in it at that time is not known.

A number of renowned Flemings have been associated with Berwick over time. For instance, Mainard the Fleming was the King’s burgess of the town in the 12th century and is credited with having laid out its plan. He was then moved to St. Andrews where he was appointed provost and had much to do with its layout also.

Later, in 1316 Flemish pirates, including John Crabbe, blockaded Berwick and the English had to move their forward supply depot back south to Newcastle.

The Fleming family prospered in Berwick. They were Freemen of Berwick and indeed the name is today displayed on the portico of Berwick Town Hall — that of Joseph Fleming who was Mayor of Berwick in the mid-19th century when the Town Hall was restored.

Jim Herbert

January 2014

Jim Herbert is a local historian who has lived in Berwick-upon-Tweed for over 30 years and works at Berwick Museum. He is especially interested in discovering and bringing to life Berwick’s rich and colourful medieval past. Through his regular blog, Berwick Time Lines, he shares some of his discoveries with the interested public.

For more about Berwick-upon-Tweed’s rich history, visit Jim’s blog at:

Web: www.berwicktimelines.tumblr.com

Facebook: Jim Herbert – Berwick Time Lines

Twitter: @berwicktimeline

References

[1] Langtoff Chronicle. Quoted in Berwick-upon-Tweed: The History of the Town and Guild (1888), J Scott.

[2] History of the Guild of Berwick-upon-Tweed, John Scott (1888)

[3] NCC, Berwick-upon-Tweed Northumberland Extensive Urban Survey

[4] History of the Guild of Berwick-upon-Tweed, John Scott (1888)

[5] http://canmore.rcahms.gov.uk/en/site/49968/details/flemington/

[6] http://canmoremapping.rcahms.gov.uk/index.php?action=do_event&event_id=711281&cache_name=aWRudW1saW5rLDQ5OTY4X3NlYXJjaHR5cGUsYWR2YW5jZWRfb3Jh&set=0&list_z=0

[7] The Red Hall; or, Berwick in 1296, Tales of The Borders, (vol. 11), John Mackay Wilson (1804-1835)

[8] http://archive.org/details/historyberwicku00shelgoog

[9] The Life and Times of Berwick-upon-Tweed, Raymond Lamont-Brown (1988)

[10] The Chronicle of Walter of Guisborough H.Rothwell (ed.) (Camden Third Series Vol.89, 1957)

[11] Willelmi Rishanger Chronica et Annales (1296), ed. H T Riley (1865)

[12] History of the Guild of Berwick-upon-Tweed, John Scott (1888)