The Flemish and the game of ‘curling’

Basically curling is a team game in which contestants slide heavy stones over a flat ice surface towards a specific target. The team that gets closest to the target is the winner. As with golf (blog posting dated November 20, 2015) there is considerable controversy over whether the game originated in Scotland or was introduced into the country by Flemish migrants. In this posting Geert and Sara Nijs examine the evidence, much of which revolves around the content of paintings dated from the late medieval and early modern periods.

The Little Ice Age

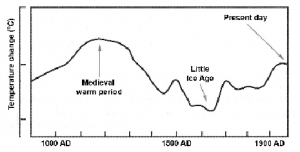

Between 1500 and 1800 temperatures in the northern hemisphere were noticeably lower than in the previous 500 years. The most severe phase, the so-called ‘Little Ice Age’ was between 1550 and 1700. Scotland and the Low Countries were among the places that experienced these lower temperatures.

During much of the Middle Ages temperatures were warmer than ‘average’. This period was followed c.1500 by a colder period with lower temperatures than average: the Little Ice Age. – Source: ‘Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Report 1990’

During this Little Ice Age many people in the Low Countries took to the frozen waters in winter to enjoy pastimes such as skating, sledging, ice dancing, walking, playing colf, etc. It is perhaps not surprising therefore that in this period the first references to the game of curling or ‘stone throwing’ occurred. The same happened in Scotland where the regular frozen ponds, lochs and rivers in winter attracted many people to the ice.1

Flanders and the game of curling

Hardly anything has been written about the Flemish and their ‘stone throwing’ game. The only early reference to a game called ‘kayuten’ or ‘kallityten’ mentioned by Cornelis Kiliaan dates from 1599.2 However the so-called Golden Age—a period of significant economic and cultural change in Flanders and the Northern Netherlands (1500-1700)—produced many paintings of life in this period showing people enjoying winter pastimes. In several of these paintings, by famous Flemish artists, people are depicted playing a Flemish game not unlike Scottish curling.1

It should be noted that no Flemish documents have been found to support the claim that people from Flanders introduced this game into Scotland.

Scotland and the game of curling

Much research has been undertaken on the early history of curling in Scotland. Curling—Scotland’s ain (own) game, as it is called—is a team game in which players slide heavy stones towards a target. ‘Brooms’ are used to manipulate the direction and the speed of the stone. The game developed at the beginning of the 17th century during the Little Ice Age. In the introduction of his book3 David B. Smith states that for centuries in Lowland Scotland the game of curling was played on loch, river and pond around Edinburgh, Stirling, Perth, etc., whenever there was ice.

Historians of curling often refer to a stone that has all the marks of a curling stone. In the stone was scratched, amongst things, the date ‘1511’. Some historians see this stone as the oldest reference to the curling game, older than any Flemish claim.4

Another old reference to the game is a document written in Latin by John McQuhin, notary in Paisley with a date of 16th February 1540/1, in which he recorded a curling challenge between John Sclater, a monk in Paisley Abbey, and Gavin Hamilton, a relative of the abbot. This involved throwing a stone along the ice three times.3

It was many years, however, until the actual word ‘curling’ was mentioned in writing. The word appeared in 1638 in a poem called ‘Muses Threnodie, or Mirthfull Mourning, on the death of Master Gall’. It takes the form of an obituary in which different objects that had belonged to the deceased are described. In this inventory curling stones were included:

‘His alley bowles; his curling stones;’

‘And ye my loadstones of Lednochian lakes’5

The oldest depiction found so far is the so-called ‘Traquair’ painting dating from around the early 18th century. It shows several well-dressed men playing the game of curling.3

Assessing the evidence

The history of curling—like that of golf—is the subject of a continuing discussion among mainly Scottish historians about the origins and development of the game. In Flanders neither the game of curling, nor its history, have been subject of much research. So what have Scottish historians found out about the history of their ‘ain’ game and the possible involvement of Flanders and the Flemish in the game?

The Stirling stone: The ‘Stirling stone’ bearing the inscription ‘St Js B. Stirling. 1511’ is, as noted above, reason enough for some historians to believe that Scottish curling is older than the Flemish game. However some experts in inscriptions assign the writing of the date and the rest of the inscription to a considerable later date. Indeed for several historians this stone is a fake.4

The rock source: On its web site the Royal Caledonian Curling Club denies any claim of Flemish involvement in the game: “It is fruitless to speculate about whether the game is Scottish in origin. Suffice it to say that the only other part of the world for which any claim has been made, the Low Countries, is spectacularly deficient in that necessary raw material, hard igneous rock, from which alone the peculiar implement of the game, the curling stone, is made.”6

The Ailsa Craig, an island in the outer Firth of Clyde, is cited as being the source of rock for producing curling stones that make the game genuinely Scottish. It is interesting to speculate whether all curling stones from the 16th century were made of this Ailsa Craig rock.

Evidence from paintings: From the beginning of the economic and cultural ‘Golden Age’ of Flanders and the North Netherlands (1500-1700) onwards, there are many paintings showing colf players on the ice. On some of these people are seen playing a game that looks like curling.

The most famous painting of a winter scene was created in Flanders in 1565 and is by the renowned Flemish painter Pieter Bruegel the Elder who lived from 1525 to 1569. See the link below. In this painting, ‘Hunters in the snow’, there is a frozen pond in the background. On the lower part of the pond there appear to be several people who are playing a game that looks similar to Scottish curling pictures from some 150 years later.

In the same year Bruegel created another painting with people playing on the ice of a river near a village. See link below. This painting called ‘Winter landscape with skaters and bird trap’ again shows several people playing the Flemish curling game.

Another less-known Flemish painter Jacob Grimmer (1525-1590), painted several winter landscapes with, in the background, a group of people playing a Flemish game that looks very much like curling. See link below.

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/b/b1/Jacob_Grimmer-Winter.jpg

From the Northern Netherlands only one drawing has been discovered so far that depicts a game of curling. It is a print from Robert de Baudous based upon a painting from Cornelisz Claesz van Wieringen made in 1615. On the right of the picture a curling match is taking place. In the foreground a broom can be seen. The players themselves are not handling brooms. It appears that the court is wiped whenever necessary. The impression is that the broom is not an integral part of the match.

During the Little Ice Age the Netherlanders also loved to play on the ice as can be seen in this drawing. It is one of the few drawings in which both colf and curling are depicted.

Winter’, Robert de Boudous after Cornelis Claesz van Wieringen, 1591-1618 – Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

The first and only painted evidence of early Scottish curling dates from the beginning of the 18th century. The painting, called officially ‘Curling’, is a winter scene and shows a frozen river in the foreground. Several people are playing the game of curling on it. Players appear to be using a broom to smooth the surface.

The background of the painting and the attire of the people are clearly Scottish but the exact location and the artist himself are not known. ‘BBC Your paintings’ (http://www.bbc.co.uk/arts/yourpaintings/) attributes it to the ‘Dutch School’. This is quite feasible as several Flemish and Netherlandish painters did go to Scotland in the 16th and 17th centuries. The painting is on display at Traquair House in Innerleithen, Peeblesshire.

A unique painting of a Scottish winter scene, called ‘Curling’. The unknown painter is probably Netherlandish. – Anonymous, c.1700 – Traquair Charitable Trust

Detail of the ‘Curling’ painting; it is the first-known painting exclusively dedicated to the game of curling. The background of the painting and the attire of the players is not Netherlandish but Scottish. – Anonymous, c.1700 – Traquair Charitable Trust

Views expressed in various publications about the origins of curling

John Ramsay of Gladsmuir was one of the first historians to raise the question of the origin of curling. In his opinion the terminology used in the game is ‘Dutch or German’. Therefore there is a strong probability that the game was brought into Scotland in the late 15th or early 16th century.7

The ‘Encyclopæedia Metropolitana’ suggests that: ‘Curling is a comparatively modern amusement in Scotland, and does not appear to have been introduced till the beginning of the XVIth century, when it probably was brought over by the emigrant Flemings.’8

According to the Scot, H. Crawford, ‘Powerful etymological evidence supports its foreign origin. The terms, being all Dutch or German, point to the Low Countries as the place whence we, at least, derived our knowledge of it. … it is supposed that the Flemings were the people who, in the fifteenth or about the beginning of the sixteenth century, introduced curling into this country.’9

When judging the paintings of Pieter Bruegel, the curling historian David B. Smith concludes that the objects used by the players certainly resemble curling stones. However the brooms, an essential part of curling, are missing.3 No information has been found about the introduction of brooms in the game of curling. The earliest written history of curling in 1541 does not mention the use of brooms. The first occurrence of brooms in the game can be seen on the Traquair House painting (“Curling”), although the ‘sweepers’ do not seem to be active in the game it depicts.

The drawing from Cornelis van Wieringen (noted above) also shows two brooms. While one of the contestants is throwing the curling stone the ‘broomers’ are passive. It is possible that brooms were only used for cleaning the court regularly and that ‘brooming’ was not yet an integral part of the game.

East Lothian minister, reverend John Kerr, concluded after examining the ‘origin’ that there is no proof of any Flemish involvement in the origin of Scottish curling. If Flemings had brought the game to Scotland in the 1500’s, he argued, why did Scottish poets and historians make no special mention of its introduction before 1600?4

Conclusion

The famous Flemish paintings from the 16th century show people playing a game not unlike the Scottish game of curling that was written about in the 17th century. Therefore it cannot be denied that in Flanders curling–or at least an early form of the game–was clearly played there. The well-documented migration of Flemish into Scotland in the 16th century could well have led to the introduction of their winter game into Scotland, but this cannot be supported by documents from that time. A remaining mystery is why Scottish artists didn’t attempt to capture in paint the players of Scotland’s ‘ain’ game, until almost hundred years after the Flemish did so.

Geert and Sara Nijs

February 2016

Geert and Sara Nijs are amateur historians who have specialised in the ancient history of the games of Flemish/Netherlandish colf/kolf, the Franco/Belgian crosse/choule, the Italian/French game of pallamaglio/mail/pall mall and Scottish golf. They are members of the European Association of Historians and Collectors (EAGHC), the British Golf Collectors Society (BGCS), the American Golf Collectors Society (GCS), and the Association Patrimoniale du Golf Français (APGF). Their publications include: ‘CHOULE – The Non-Royal but most Ancient Game of Crosse’ (2008) and its revised French edition ‘Jeu de Crosse – Crossage A travers les âges’ (2012), ‘Games for Kings & Commoners’ (2011), ‘Games for Kings & Commoners Part Two’ (2014) and ‘Games for Kings & Commoners Part Three’ (2015), the final part of the trilogy.

For more detailed information about the history of the continental golf-like games and Scottish golf see their website www.ancientgolf.dse.nl where you also find their email address.

Bibliography

(1) Geert & Sara Nijs, Games for Kings & Commoners Part III; Saint Bonnet en Bresse, Editions Choulla et Clava, 2015

(2) Cornelis Kiliaan, Etymoligicon Teutonicæ Linguæ; Antwerpen, Ioannem Moretum, 1599

(3) David B. Smith, Curling: an illustrated history, 1981

(4) John Kerr, History of Curling, Scotland’s Ain Game and Fifty Years of the Royal Caledonian Curling Club, 1890

(5) Henry Adamson, Muses Threnodie: or Mirthful Mourning, on the death of Mr Gall. Containing Variety of Pleasant Poetical Descriptions, Moral Instructions, Historical Narrations, and Divine Observations, with the Most Remarkable Antiquities of Scotland, Especially of Perth, 1938; reprinted in Perth by George Johnston, 1774

(6) www.royalcaledoniancurlingclub.org

(7) An account of the game of curling. By a member [John Ramsey, Preacher of the Gospel] of the Duddingston Curling Society, 1811

(8) Encyclopædia Metropolitana; or, universal dictionary of knowledge, Vol XVII; London, William Clowes and Sons, 1817-1845

(9) H. Crawford, A Descriptive and Historical Sketch of Curling: Also, Rules, Practical Directions, Songs, Toasts, and a Glossary; 1828