In the Name of the French Father

This blog posting, prepared by Dr Maarten Larmuseau, describes how a study of surnames led to genetic proof for a 16th century migration of French Catholics to Flanders. The work demonstrates, among other things, the fluidity in movement of the population of Flanders in medieval times.

Migration from and to Flanders

Flanders suffered a serious population decline between 1570 and 1600 as a result of war, disease, and emigration to Holland, England, Scotland, Germany, and other countries. Religious and economic uncertainties were the main drivers for these migrations. Many Flemish families had turned to Protestantism and after the so-called Iconoclastic Fury — or the Beeldenstorm in the Dutch language (see figure 1) — and the Fall of Antwerp in 1585 they were forced by the governor of the Netherlands, Alexander Farnese, to leave Catholic Flanders. The Iconoclastic Fury describes a phase that involved the destruction of Catholic religious images.

Using archival documents, it is possible to estimate a population decline for Flanders of about 30 to 50% between 1570 and 1600, taking regional and local differences into account. In some regions, the estimations even point to a decline of two thirds. Once thriving towns, villages, and homesteads felt the impact of this depopulation. As a consequence, many northern French Catholic families left for Flanders to repopulate this region.

Archival documents dating back to this period have been found in which priests complain of their inability to communicate with large numbers of new parishioners who only spoke a French dialect. It is estimated that about 10% of the Flemish families at the start of the 17th century had French roots. After a few generations, these families seem to have been completely integrated.

During the Council of Trent (1545–1563) the Church decided to keep record of baptisms, marriages, and burials in parish registers, but it was not until the early 1600s that these registers were introduced in the Low Countries. As a result there is very limited genealogical data available for the period covering the migration. On the other hand, surnames transmitted from father to son have been in use since the 13th and 14th centuries in Flanders and northern France. The many French surnames in Flanders, whether or not transmuted to a Flemish variant (e.g., Ghesquires, Spincemaille, Carbonelle, and Seynaeve), are likely to be the only remnant of a northern French immigration at the end of the 16th century. Or can genetics provide additional proof?

Genetic Analysis of Flemish Men

Thanks to the genetic genealogical project organised by Familiekunde Vlaanderen (the Flemish Family History organisation) and the KU Leuven (University of Leuven), genealogical data and DNA of more than 1,500 Flemish men have so far been collected and analysed. This project is of great scientific importance in tracing the genetic roots of the Flemish population, in observing regional differences within Flanders, and in identifying the genetic history of the medieval migrations. The Y-chromosomal results are also of interest for genealogists in identifying relationships between participants and in providing data that can verify and complement family trees.

Extensive genealogical and archival research permitted an accurate selection of suitable candidates to support the genetic work on the northern French migration to Flanders at the end of the 16th century. The selection consisted of 549 Flemish men possessing an authentic Flemish surname and 50 with a French (Roman) surname. The oldest reported paternal ancestor in all the families with a French surname lived in present day Flanders, but the surname was not present in Flanders before 1575.

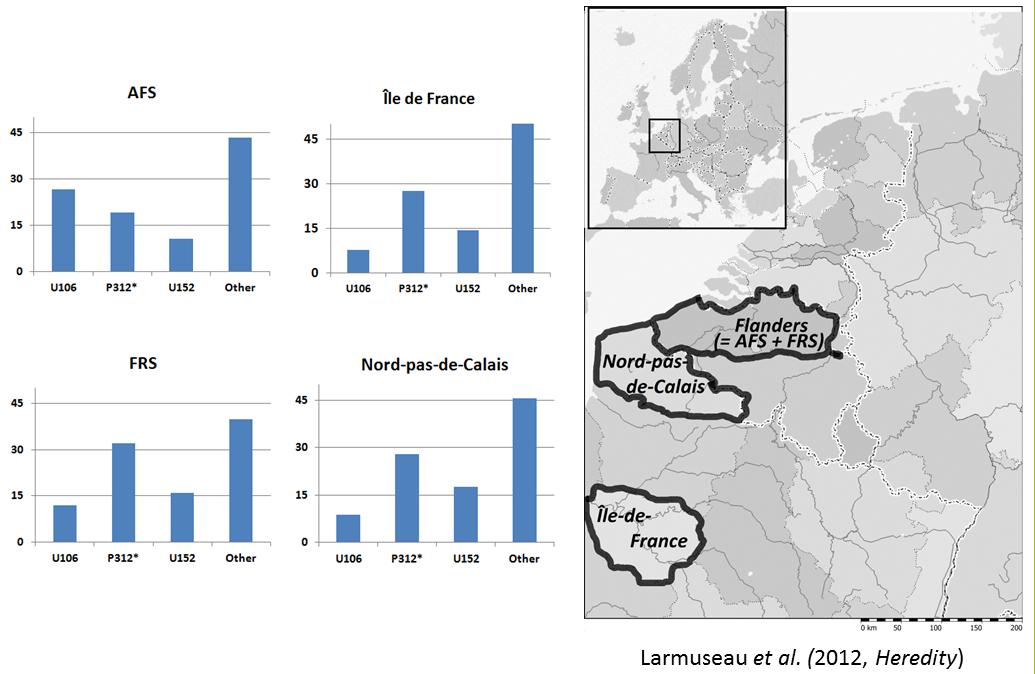

The Y chromosome for all 599 selected men was investigated. It is the human sex-determining chromosome and is transmitted from father to son – just like family names. After having been genotyped on the Y chromosome, the individuals were allocated to different evolutionary lineages (the so-called haplogroups). As a comparison, the haplogroup frequencies of approximately 160 Frenchmen with a French surname from two northern French regions (Nord-Pas-de-Calais and Île-de-France) have been included in the analysis.

Next, the haplogroup frequencies of the four different groups (Flemish surname, French surname, Nord-Pas-de-Calais, and Île-de-France) have been compared. A statistically significant difference exists between the Flemish men with an authentic Flemish surname and the Flemish men with a French surname. Also, there was a difference between the Flemish men with an authentic Flemish surname and the two groups of Northern Frenchmen (Figure 2). However, no significant difference exists between the Flemish men with a French surname and the two groups of Northern Frenchmen. From this, we were able to conclude that a migration that occurred more than four hundred years ago from Northern France to Flanders left traceable genetic marks on the Y chromosome in the current Flemish population.

Conclusion

This study yielded several findings of scientific importance. First of all, it proves that genealogical research combined with Y chromosomal analysis can contribute to the reconstruction of historical events. The observed differences in Y chromosomal haplogroup frequencies between Flanders and the adjacent northern France shows the potential to detect genetic signals of historical events. Next, the study demonstrates that though non-paternity – namely adoption or a child born out of wedlock – occurs every generation in approximately 1 % of all live births, a link can still be found between the origin of the surname and the Y chromosome after four hundred years. Lastly, the research offers genetic proof that the surname can provide information on past migrations that a family participated in even when no genealogical information can be found for the time when the surname has come into existence.

Dr Maarten Larmuseau

January 2016

Dr Larmuseau is a researcher at the Laboratory of Forensic Genetics and Molecular Archaeology at the University of Leuven, Belgium.

Reference

The above blog posting is based upon the scientific publication, ‘In the name of the migrant father – Analysis of surname origins identifies genetic admixture events undetectable from genealogical records’, by Larmuseau et al. It is available from the website of the journal Heredity: http://www.nature.com/hdy/journal/v109/n2/full/hdy201217a.html.