The Flemings of Pembrokeshire

As noted in earlier blog postings (see especially posting dated November 21, 2014) some of the Flemings that came to Scotland had, according to historical records, done so after a period of time spent in Wales. This blog posting by Pamela Hunt examines why the Flemings had come to Wales and describes an ambitious project that seeks to restore an old Flemish church and gain a better understanding of the Flemish footprint in Pembrokeshire.

In one extract of William of Malmesbury’s “Chronicle of the Kings” written in 1125, there is a passage that caught the eye of the Pembrokeshire village of Llangwm’s Local History Society:

The Welsh, perpetually rebelling, were subjugated by the king (Henry 1 1100-1135) in repeated expeditions, who, relying on a prudent expedient to quell their tumults, transported thither all the Flemings then resident in England. For that country contained such numbers of these people, who, in the time of his father, had come over from national relationship to his mother, that, from their numbers, they appeared burdensome to the kingdom. In consequence he settled them, with all their property and connexions, at Ross, a Welsh province, as in a common receptacle, both for the purpose of cleansing the kingdom, and repressing the brutal temerity of the enemy1.

The village of Llangwm is in that province of Ross and sits on the banks of the Cleddau Estuary. It is known to have been a winter haven for the Vikings who would draw their ships up onto the foreshores for repairs during the 10th and early 11th century. They called the place Langheim, loosely meaning Long Road, Long Street or Long Way. Many Vikings settled in this part of the world, indeed the parish to the north is called Freystrop, a derivation of Freya’s Thorpe. Freya is the Norse Goddess of Love and Thorpe is a village or hamlet. There are many communities in South Pembrokeshire that have Viking names. This is the area referred to by William where England’s Flemings were sent to help the Normans keep order.

William of Normandy’s marriage to Matilda, Princess of Flanders, meant that the Flemish became allies to the Normans and indeed Flemish nobles joined the 1066 expedition to invade England. With the success of the invasion some Flemish knights were given land and estates in England. When Henry I became king in 1100 he perceived a troubling superfluity of Flemings (probably disbanded mercenaries and others)2. So with one stroke Henry solved two problems. He sent the Flemings to Pembrokeshire with promises of land there. But more importantly they could help to keep order. As William of Malmesbury attests, the Welsh were constantly rebelling. It is believed that as many as 2,500 Flemings were sent to Pembrokeshire.

But this wasn’t the only migration to Pembrokeshire during Henry’s reign, it seems there was another. According to the Welsh Chronicle of the Princes, or the ‘Brut y Tywysogion’ written around 1350, it refers to ‘An inundation across the sea of the Britons, flooding vast areas of Flanders wetlands’3. It goes on to suggest that this was a reason for there being Flemings in Pembrokeshire. But it doesn’t tell us when during Henry’s reign this happened. Professor Tim Soens of the University of Antwerp specialises in the history of Flanders Hydrography and he confirmed that there was a massive storm surge in October 1134 causing dozens of Wetland villages to be washed away and thousands killed. Was it out of kindness or a determination to reinforce his hold on South Pembrokeshire that Henry chose to invite the survivors of that catastrophe to settle in Pembrokeshire?

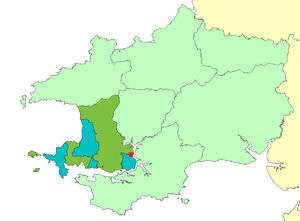

The Normans established a Cordon Sanitaire with a string of castles that stretched from Newgale in the west to Laugharne in the east. This became known as the Landsker Line. Those Welsh who refused to accept Norman rule were forcibly moved north. Up until the end of the 19th century, the area to the north was referred to as ‘The Welshry’ and they would refer to the south as ‘Down Below’. Even today, journey a mile or so north of the Landsker and you will find Welsh being spoken, but it will be hard to hear Welsh spoken to the south of the Landsker.

In an article written by the Methodist Minister posted to Llangwm in 1864, he described the people of Llangwm as Hardy fishermen and women. He went on:

The customs that prevail in this community are peculiar. Separate and distinct from the Welsh race, they claim descent from the Flemings who landed at Milford and took possession of that town and also of Haverford and possessed themselves of the surrounding country in the reign of Henry 1. From that time to this, they have retained their distinctive character. You need not ask them the question so often asked in the north of the Principality ‘Fedrwch chivi siared Saesneg?’ (Can you speak English?) As all of them are essentially English, so far as their language is concerned. These people, though now for the most part on a level with their Welsh neighbours have retained for them, and their language, a hereditary contempt4.

He goes on to write that they will have nothing to do with those who live in the Welshry. He noted too that the women, having chosen their husband rather than the other way round, would then retain their maiden name after marriage, something that still occurs in the Flemish speaking areas of Belgium and Holland today. Those 19th century people of Llangwm, still boasting pride in their Flemish ancestry used also to refer to the ‘Dolly Roach’ family being lords of the manor during medieval times. They were referring to the De La Roche family who had lands both at Llangwm and further north at Roch. That is when Godebertus Flandrensis became a person of considerable interest. It turns out that he was the ‘patriarch’ of the dynasty that became the De la Roches. Very little record of him survives and one of the goals of the project is to find out exactly who he was.

There are many places ‘below the Landsker’ that can claim a strong Flemish past: Tenby, Flemingston, Wiston, Walwyn West and Tancredston for instance. But it’s Llangwm, in spite of the village’s Welsh name, which seems to retain one of the strongest links with its medieval Flemish past. And what of that name? It’s only the thirteenth name by which this community has been called since the Vikings came! Other names dating from 1200 include Landegunnie, Landigan, Langham, Langomme and Langum, but barely 30 years after that Methodist Minister wrote his piece, a Welsh speaking Rector appointed to St. Jerome’s Church decided that Langum, the name the village had been known since the 1600s, was a distortion of the Welsh Llan Cwm, meaning Church in the Valley. So the village’s name was changed once more.

This had for centuries been a remote and insular village and marriages outside the community were discouraged. Many of those residents wouldn’t have even ventured as far as Haverfordwest, except of course the Hardy Langum Fisherwomen who would carry baskets of herring, mussels, cockles and oysters to sell at the market there as well as at markets in Tenby and further afield.

Llangwm’s Flemish past had largely been forgotten until quite recently. The urgent need for major repairs to Llangwm’s Church of St. Jerome unexpectedly provided a special opportunity to rediscover those roots. St. Jerome’s had been built by Flemish craftsmen around 1185, but in recent years the fabric of the building began to deteriorate quickly. In 2013 a bid to Heritage Lottery for development funding for a project that would combine the repairs and renovations with research and an exhibition was successful. That development led to a full second stage bid a year later and that has been successful too. The project is expected to commence in July 2015.

The primary aim is to discover as much as possible about Godebertus Flandrensis and his descendants, who changed the surname two generations on to De la Roche. Another goal is to find out when the family settled in the area and to discover more about the church and how it has changed over the years. Then with all that information gathered it is hoped to create an exhibition in the North transept of the church with a locally designed and sewn tapestry. Modern communications techniques will be used to tell the story.

This funding will allow researchers to visit the National Archive at Kew, the British Library and other sources of written research material and spend time checking out writings related to the De la Roche family, and the village. The funding will also support archaeological research at the site of a medieval manor house at the edge of the village, which may also have secrets to share. In addition there will be funds that will allow six male volunteers, who can confirm that their families have lived in this area for at least 250 years and that the male line of that family is unbroken, to have their DNA tested, hopefully to discover that they do have Flemish Ancestry.

The project will be a significant challenge. It could be described as a 500-piece jigsaw that has, perhaps, 300 pieces missing. The objective is to find as many of those missing pieces as possible.

Below is a list of issues that it is hoped that research will shed light on:

1. We know that Godebert was born in 1096, ten years before Henry 1 sent the Flemings out of England. Most genealogy sites suggest he was born in Pembroke, but one states Flanders. If he was born in Pembroke that suggests that his father took part in that initial invasion of South Wales in 1087. Yet it is known that the Normans looked down on the Flemings. As a result, the Flemings were eager to adopt Norman lifestyles and to be seen to be more like them; this is the reason that Godebert’s grandsons adopted the De la Roche surname. If his father was part of that invasion, who was he? And what was so special about him that the Normans allowed him to join that invasion?

2. Godebert named his sons Richard and Robert, the same names as the younger brothers of Mathilda Princess of Flanders. Was he possibly a relation of the ruling family of Flanders?

3. Who was the first of that family to settle in Llangwm? The 12th century dovecote at Great Nash Farm and the site of the medieval manor house suggests that it must be one of the first three generations – Godebert, his sons Richard or Robert, or indeed Robert’s eldest son David De la Roche. Richard died with no heirs.

4. Yet in “The Greatest Knight”, the biography of William Marshall, the author Paul Asbridge refers to this particular David De la Roche betraying William Marshall over lands in Leinster. If David lived in Leinster at that time, then who was living in Llangwm?

5. Why indeed did that family create an estate in Llangwm? It is four miles south of the Landsker Line. Surely the lands that were granted to the Flemish nobles would have been closer to the defensive line and it is known that Adam, Robert’s youngest son completed Roch Castle in the 1180s. So when was the Llangwm estate occupied and by whom? The first recorded De la Roche presence is David Lord of Landegunnie and Maenclochog in 1244.

6. The De la Roche’s were active in the conquest of Ireland. The Norman French poem, “The Song of Dermot The Earl” refers to Godebert’s eldest son Richard going to Ireland to help Dermot regain his lands with his small private army two years before Strongbow’s invasion. He failed that time and was back in 1169 with Strongbow’s force. He then died, reportedly in Wexford, with no male heir in Ireland, enabling his lands to pass to Robert’s sons. So who had what?

7.It is also known that the Flemish nobles Wizo and Tancred went to Scotland to establish Flemish communities. Did they return to Pembrokeshire? If so when?

8.There is also a suggestion that Godebert too went to Scotland, but we can find no evidence of this trip. Anyway the 1130 Court of Rolls states that he was awarded lands in Pembrokeshire on a payment of 126 shillings. He is reported to have died in 1131 at the age of 35. So when could he have undertaken what would have been a very long trip?

The research is still at the point where more questions are being raised than are being answered. There is much work to be done and it is hoped that by tying in with with the Flemings in Scotland and the Flemish People Project, more of the jigsaw pieces will be put into place.

Pamela Hunt, May 2015

Pam Hunt chairs the Heritage Llangwm working group and has been responsible for raising most of the £420,000 needed to complete this project. She retired to Llangwm in 2006, having spent her working life in broadcasting and television production, joining the BBC as sound effects technician on The Archers in 1968. She left the BBC in 1990 and started her own television production company, producing documentaries usually with a history slant until her retirement. She was intrigued by the fact that Llangwm’s church had two effigies and some intricate Norman carvings in what appeared to be little more than a rural Victorian church.

References

(1) The Chronicle of The Kings of England – William of Malmesbury 1125, http://archive.org/stream/williamofmalmesb1847will/williamofmalmesb1847will_djvu.txt

(2) J. Arnold Fleming, Flemish Influence in Britain, Vol 1, p.59. Glasgow, 1930

(3) Brut y Tywysogion (The Chronicle of the Princes) – Caradoc of Llancarfan, c1340, http://archive.org/details/brutytywysogiono00cara

(4) Langum, “A Village in The Little England Beyond Wales” Unknown Methodist periodical written by M.C. in 1864 and held at The National Library of Wales

We ( my Fleming family ) were told all our lives that were of an American Indiana (Cherokee nation) descent. We have our own cemetery library so you can imagine the shook that ( DNA came back)we are a direct pedigree of Lord Montrose . Thank you! Sandra Marie Fleming